Article

India’s 8.2% GDP Jump, Strong Growth, But a Balanced View

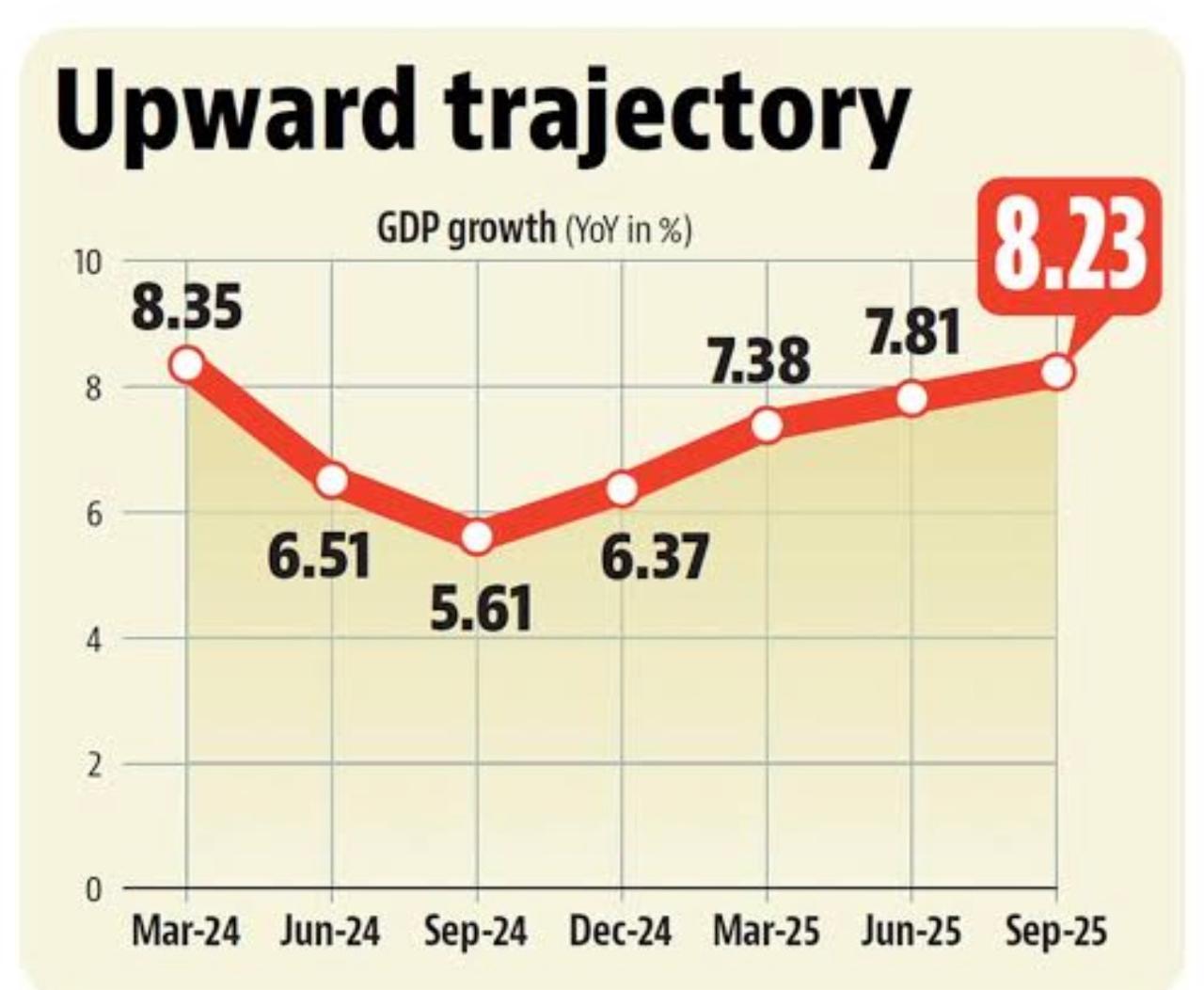

In the latest data release, India’s economy recorded a real GDP growth of 8.2% in the July, September quarter of 2025, marking the fastest pace in six quarters.

In the latest data release, India’s economy recorded a real GDP growth of 8.2% in the July, September quarter of 2025, marking the fastest pace in six quarters. On the face of it, the numbers are impressive, and better than most economists had predicted (many had forecast around 7.3%).

But beyond the headlines lie important questions. Several analysts argue that this “growth surge” may overstate actual economic realities, especially given how the informal/unorganised sector is estimated.

Where the Strength Seems to Come From

On the output side, both industry and services posted solid gains: manufacturing was up, 9.1%, construction rose, 7.2%, while services including financial & real estate, professional services surged.

On the consumption front, private final consumption expenditure (PFCE) grew by 7.9%, a boost even before the full impact of recent tax and policy changes.

Lower inflation, a favourable “GDP deflator,” and the base effect (i.e. last year’s lower growth in the same quarter) have added a statistical lift to the real-GDP number.

Many economists and policy-makers highlight that reforms, stable domestic demand, and government investments have helped sustain momentum, even as global headwinds, e.g. tariffs, export pressures, intensify.

Taken together, the data reflect a broad-based expansion: consumption, manufacturing, services, and investment all appear to have contributed.

The Skeptics, Why Some Economists Doubt the “8.2% Surge”

Not everyone is convinced the 8.2% number reflects genuine, widespread economic improvement. Critics raise several concerns, especially around how the unorganised sector is treated in national accounts. Some of the key arguments:

As argued by economists such as Arun Kumar and former official statistician Pronab Sen, the methodology used to estimate output from the informal/unorganised sector may be flawed, often using proxies based on organised-sector performance. This can lead to overestimation of output when the formal sector does well.

Because much of the informal economy does not maintain formal records, does not pay GST or corporate taxes, and lacks timely reporting, official estimates rely heavily on assumptions and extrapolations rather than real-time data.

According to this line of criticism, the headline number (8.2%) may be “structurally misleading”, especially if unorganised-sector activity is actually stagnating or shrinking. What may be growing is mostly the formal sector, which then gets mis-used as a proxy for the rest.

Some high-frequency indicators, such as consumer‐goods sales, durable-goods output, automobile or two-wheeler sales, reportedly have not shown a comparable surge. That raises doubts about whether the GDP jump is reflected in ground-level economic activity.

In short: if official proxies over-estimate the output of informal enterprises, the 8.2% number may paint a more optimistic picture than reality, at least until more robust data from the unorganised sector becomes available.

ARKa Invest’s Take - Both Hope And Caution

The 8.2% growth figure is encouraging, and there are reasons to believe the Indian economy is doing relatively well: strong manufacturing numbers, healthy consumer demand, and supportive macro policies certainly point to resilience.

But numbers, especially aggregated national accounts, are inherently blunt instruments. When a significant portion of the economy (the unorganised sector) is estimated rather than measured, the official growth rate must be interpreted with caution. Until better, more direct data from informal enterprises (small manufacturers, unregistered services, micro-firms, self-employment, etc.) becomes available, there remains a real risk that growth, especially its distribution and ground-level impact, is being overstated.

Thus, while the 8.2% growth should be welcomed as a sign of strength, it should not be treated as incontrovertible proof that “everything is back to normal.” For many, particularly those employed in the informal economy, the benefits may not be as tangible.

In our view, policymakers and analysts should treat such high quarterly GDP numbers as one of several indicators, not the only one. Complementary data (employment statistics, rural/urban consumption trends, small-enterprise output, income growth, household surveys) must be given weight if we want a fuller, more realistic picture of the economy.